DIVING INTO HISTORY (PART 3)

October 25, 2022

In June of 1821 Dr. Erastus Richardson was appointed Surgeon of the 3rd regiment of the infantry, 23rd Brigade, 3rd division of the Militia of the State of Maine. Two months later, in August, Mary bore their first child, a boy. Named for his father’s, father and mother’s family they would call him, Amasa Johnson. Sadly, just 5 days later, as was all too often the case in those days, misfortune would visit the fledgling family. Childbirth was always a perilous and risky time. Young Amasa died, no doubt causing great heartache to Erastus and Mary.

They would forge ahead and in late September 1822, Erastus purchased land on the corner of Washington and High Streets, in the shadow of Fort Sullivan Hill. He paid local merchant, Benjamin Smith $215. 82 for the parcel. The property had once been part of a much larger tract of land first purchased in 1774, by one of Eastport’s original settlers, Caleb Boynton, of Newburyport, from the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. It is likely work was begun on a new federal style, post and beam cape shortly thereafter.

After the Revolutionary War there was a period of good feeling. One way this was expressed was in the architecture of the new republic. The heavily ornate Georgian style that emanated from England and was named for the king the patriots so vehemently opposed, was modified, while maintaining its classical roots, to a more delicate restrained symmetry. Elements found in archeological discoveries of the time in Herculaneum and Pompeii were introduced.

Urns (signifying death and resurrection), acanthus leaves (eternal life) and lion’s heads (courage and protection); these motifs and more would find their way to the house on Washington Street; specifically the grand front door.

The fan window above with its black lead tracery form an arch of fourteen hearts divided by a roman urn. Thirteen gilded stars surely symbolize the newly formed 13 united and free states of America. One has to wonder if the urns, two more of which can be found in the sidelights, and the string of hearts have any connection to their lost first born. Could they be a heart-filled tribute to their deceased son? A single additional star caps the upper urn, a symbol of resurrection

On March the 17, 1823, while work on the federal was likely still going on, a second child, Mary Lydia was born. A year and three months later, on Independence Day, Mary Lydia would pass away striking another blow to the young couple. Succumbing to any one of a plethora of diseases, nearly half of the children born in this era would not make it to their fifth birthday.

There in a house on Shackford Street in Eastport, that sports a front doorway that is surprisingly similar to our Washington Street project, with its lead tracery and classical ornament on sidelights and semi-elliptical fan window. It is significant that the acanthus medallions, that punctuate throughout, are an exact match to those on Erastus’s old home. They were without a doubt cast from the same mold. An item from the Eastport Sentinel, 1882, suggests a construction date of 1824.

Looking at the home today with its austere white façade; only the multi-colored glass in the federal door surround hint at the flamboyant color palate that once adorned the building; a reflection of the personality of the home’s first occupant.

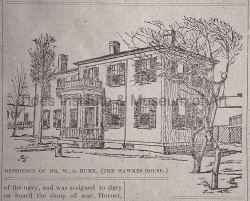

This was, at its earliest incarnation, the residence of another distinguished Eastport doctor and contemporary of Erastus, Micajah Hawkes. A graduate of Brown University, Hawkes came to Eastport in 1817. In June of 1824, just a month before his daughter’s passing, Erastus was called to the stand to testified in the esteemed doctor's malpractice trial; a case both celebrated and historic in the annals of medicine.

In the town of Lubec, in September of 1821, Charles Lowell was thrown by his spirited horse as it reared and fell back upon him, dislocating his left hip. His physician, John Faxon, unable to perform a necessary correction called in the more experienced Hawkes from Eastport for assistance. Hawkes, believing he had successfully relocated the hip left things in Faxon’s hands. The following week, he returned and ascertained that Lowell was indeed on the mend.

When Micajah visited Lowell a month later, he found that the hip was again seriously out of joint; a condition he suspected to have been caused by the patient not properly following his doctor’s orders. Hawkes said he would return shortly but did not claiming he was, “detained by important cases.” When he did return two weeks later it was with Dr. Shelomith Stow Whipple, a friend who had recently arrived from Boston with the intention of settling in Lubec. Both men determined that nothing could be done.

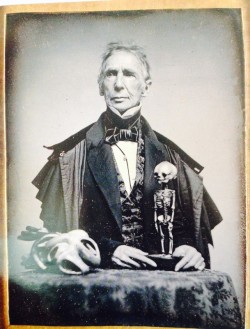

Lowell “erupted in anger and swore vengeance on the physicians who had ruined him.” He traveled to Boston’s Massachusetts General Hospital to seek the opinion of chief surgeon, John Collins Warren, one of the most prominent surgeons of the day. Warren diagnosed “a dislocation of the femur downward and backward into the ischiatic notch” and determined that that there was no remedy save a dangerous, life-threatening surgery. After consulting with several other doctors including Willian Ingalls, Erastus’s old professor and “natural” bone-setter, Robert Hewes, Lowell left Boston vowing to sue his doctors in Maine.

The lawsuit, Lowell vs. Faxon and Hawkes, involved three trials over several years. In June 1822 a jury submitted a verdict in favor of Lowell. Micajah and Faxon’s appeal in September resulted in a hung jury. The final trial, in 1824, was the most involved, with many physicians testifying including Erastus Richardson and the celebrated surgeon, John Warren. Erastus was brought in as a fact witness to impeach Micajah’s claim that he was “detained by important cases” In addition to medical opinions about the case, his testimony amounted to the simple assertion that he or others could have covered for Micajah, if he had any need to get away; confessing that he was not friendly to Dr. Hawks.

The case ended when Lowell, bankrupted by the litigation, was convince to withdraw; with the court concluding that because there was no medical consensus on the proper treatment, both doctors had been “professional and competent.”

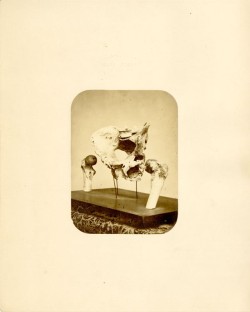

At Lowell’s request, an autopsy was performed upon his death in 1858. Jonathan Warren, the famous surgeon’s son, with the family’s consent, brought the hip back to Boston. It remains there today, preserved in the Warren Anatomical Museum at Harvard University.

(click photo to view larger image)

|

|

|

|

(comments = 0)

leave a comment

fineartistmade blog

A journal about home design, gardening, art & all things Maine. Read more...

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- November 2021

- May 2020

- October 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- September 2018

- April 2018

- December 2017

- August 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- December 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- April 2016

- November 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- March 2015

- October 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- July 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- August 2012

- June 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- October 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- My Scandinavian Home

- Daytonian in Manhattan

- {frolic!}

- I Married An Irish Farmer

- Smitten Kitchen

- The Curated House

- even*cleveland

- Mary Swenson | a scrapbook

- Ill Seen, Ill Said

- Gross & Daley Photography

- Remodelista

- Abby Goes Design Scouting

- Mint

- the marion house book

- 3191 Miles Apart

- Svatava

- Katy Elliott

- Poppytalk

- Kiosk

- decor8

- KBCULTURE

- Lari Washburn