.jpg)

Ye Ole Rim Lock

December 10, 2013

Often when we drive up the hill on Calais Avenue, I think of early 1900s era picture postcards I've come across in antique shops. Depicted were this scenic pair of streets, divided by a wide green park-like boulevard, lined with an arched canopy of majestic elms. In the mid-nineteenth century these avenues were also graced with the large elegant homes of many of Calais's more prosperous residents. While most of those iconic trees are gone, many of the classic old homes have been spared. One such Federal gem has been fully refurbished by Alan & Candace Dwelley and is now serving travelers as the Greystone Bed & Breakfast. This circa 1837 home is one of two built (side by side) by Abner Sawyer, an affluent local merchant, as wedding gifts for his daughters, Mary and Almeda. The property is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

We were called in for one of our specialties - the restoration of their impressive, guest welcoming, front door. This imposing six paneled bit of joinery, likely hand made on site, had a smattering of different hardware eras; an ornate Victorian mail slot, what was left of a 1920s hand operated door bell, an 1880s crystal door knob, an early sand cast, brass shield knocker, the original cast iron butt hinges stamped A. K. & Sons and the pièce de résistance - an impressive face mounted, rim lock with its accompanying keeper, solid brass interior door knob and oval keyhole escuteon. The lock was quite large, fitting for the ample sized door it adorned - everything but the brass knob was painted black. We suspected that some of the elaborate raised elements and the edge of the keeper might be solid brass. Once we got the door to our workshop we could begin to expose its secrets.

It turns out that the door had been stripped before but now had several layers of more recent paint - most notably a green and a pink under the interior white and exterior blue. A combination of heat gun and chemical stripper would remove that along with a lot of gooey latex caulk and paint build up that were obscuring molding details. Remnants of the original faux grained mahogany (a popular 19th century interior finish) still survived under early hardware that had never been removed. The lock's exterior knob would have been solid brass like the interior with a brass rosette, but that had been 'upgraded' (probably in the 1880s) with crystal. The sweet brass keyhole escuteon was likely purchased as part of the rimlock package; its four tiny brass tacks were carefully removed for stripping to be put back in their original holes later.

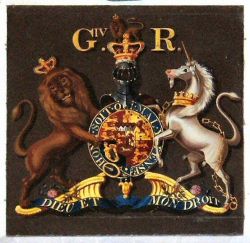

Now, what we were really curious about - that intriguing rim lock & keeper. Removing later layers of black paint brought out all kinds of detail. Indeed the edge of the keeper was solid brass, quite ornate; with a wonderfully preserved ancient patina (we would never polish that off). We could see words engraved on the keeper, CARPENTER PATENTEE, in a serpentine configuration flanked on either end by matching hallmarks - the initials GR with a crown above each set. The rim lock itself sported a brass medallion that looked like a coin about the size of a quarter. It was embossed with CARPENTER & CO. PATENTEES around the edge and a tiny coat of arms in the center. Following these telltale clues would take us on a journey "across the pond," to the beginnings of a revolution.

It was obvious that the lock was not American made but of British origin. The hallmark GR topped by a crown translates into the reign of King George of England. Taking a loupe to the tiny coat of arms one could make out a lion and a unicorn holding a shield topped with a crown. After a little digging it turns out that this solid brass seal was a simplified version of the royal coat of arms - the lion wearing a crown supporting the left side of the shield represents England with the unicorn on the right representing Scotland.

The other part of the equation, that serpentine CARPENTER PATENTEE that slithered down the keeper. It turns out this refers to the locks patent owner, James Carpenter, a prominent locksmith in Willenhall, England, "the town of locks and keys." This ancient, Saxon, lock-smithing town sits squarely in the heart of 'Black Country' a region near Birmingham that emerged in the 1830s as the first industrial landscape anywhere on the planet. The area soon received its distinctive name because of a blanket of black soot produced by heavy industries that covered and oftentimes choked the vicinity.

Thanks to an abundance of iron ore, limestone and coal - metalworking started in the region as early as the 16th century. Local people in the mostly agrarian society augmented their incomes during slow periods by working as "smiths" producing by hand; nails, grid irons, curry combs, bolts, locks, latches and coffin handles. Dud Dudley, an English metallurgist, wrote in his 1665 book, Metallum Martis, that in the 1620s "Within ten miles of Dudley Castle there were 20,000 smiths of all sorts and many iron works..." In 1618, at the age of twenty, Dud took charge of his father, Lord Edward Dudley's, furnace and forge and was one of the first to smelt iron ore using coke, a fuel derived from coal. By 1770, Willenhall boasted as many as 148 skilled locksmiths, a specialized outgrowth of blacksmithing.

Our locks inventor, James Carpenter, was born in 1775 and came to Willenhall at a young age. In 1795 he began to hone his skills in the art of ironmongery. In 1830, with fellow inventor, John Young of Wolverhampton, Carpenter took out Patent Number, 5880 for an improved design of the latch bolt and mortise lock. The two agreed to divide the patent into rim lock and mortise lock use. While Young chose to produce the mortise locks, Carpenter went on to construct the rim lock naming it "Number 60." His popular invention, commonly referred to as "Carpenters lift up lock," renewed the vitality of Willenhall's principal industry. He was discribed as, "one of the most enterprising lock makers of the district and one of the first to apply machinery to aid in their production."

As his business grew he erected a large factory on New Road, Summerford Place Works, one of the most extensive lock factories in England. Carpenter died in 1844 and his son, John and son-in-law, James Tildesley took over the factory changing the name to Carpenter & Tildesley. Tildesley wrote in a letter that his father-in-law, "obtained considerable celebrity in foreign markets for the articles he manufactured."

All things considered it appears our "Greystone Carpenter lock was manufactured between 1830 and 1844 - likely before 1837 the year the home was built.

The Carpenter lift up rim lock has a distinctive lever-type striker that rides up a diagonal incline on the keeper and drops into the latched position rather than withdrawing into the case as with most rim locks. It was made of heavy iron with solid brass trim manufactured in England primarily for export to America and the British Colonies. It's sophisticated locking mechanism and bolt was enclosed in a hand forged and filed iron box which was screwed to the face of the interior of the door. When the doorknob is turned the latch bolt lifts up and out of the keeper - hence the need for the cutout keeper.

There is a simple reason why our lock is English and not American. According to one historian, "The manufacture of these complex mechanisms required skill in forging the fixed and moving parts of the lock and in hand-filing each moving piece to the close tolerance required for smooth and faultless operation." In short, it required British craftsmen. This was a condition created during the colonial era in America. The Crown intent on maintaining a manufacturing monopoly, took action to prohibit American production including a ban on the export of machinery to the colonies and a policy that such skilled English craftsmen could not leave the country. Colonial craftsmen were confined to the repair of iron items and the manufacture of simple nails, hinges and latches. It would take some three decades after the War of 1812 for the United States and the American Industrial Revolution to finally catch up.

With all this Black Country digging - that other bit of "door furniture," those cast iron butt hinges stamped A.K. & Sons, came to mind - I had to follow up. A.K. it turns out were the initials of another of the region's iron founders, Archibald Kenrick (1760-1835). Originally a buckle maker, Archibald built an iron foundry in West Bromwich in 1791. What was more surprising to learn was that A. Kenrick & Sons Ltd. is still in business today at the very same address - 222 years later.

Thanks to Black Country Living Museum for their assistance.

For more photos of the project click here.

(click photo to view larger image)

|

|

|

|

(comments = 1)

Wow thank you for this excellent well researched material. I have to replace a worn interior brass part on our front door and this helped me out greatly. Much appreciated.

leave a comment

fineartistmade blog

A journal about home design, gardening, art & all things Maine. Read more...

- June 2025

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- November 2021

- May 2020

- October 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- September 2018

- April 2018

- December 2017

- August 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- December 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- April 2016

- November 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- March 2015

- October 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- July 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- August 2012

- June 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- October 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- My Scandinavian Home

- Daytonian in Manhattan

- {frolic!}

- I Married An Irish Farmer

- Smitten Kitchen

- The Curated House

- even*cleveland

- Mary Swenson | a scrapbook

- Ill Seen, Ill Said

- Gross & Daley Photography

- Remodelista

- Abby Goes Design Scouting

- Mint

- the marion house book

- 3191 Miles Apart

- Svatava

- Katy Elliott

- Poppytalk

- Kiosk

- decor8

- KBCULTURE

- Lari Washburn