The Springs

December 20, 2012

"What's in a name? That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet." Juliet's sentiment was entirely understandable and continues to be relevant. What did it matter whether you were a Montague or a Capulet - if you were in love?

But as Shakespeare well understood - sometimes a name can carry within its vowels and consonants significant meaning. Case in point - the naming of our stuff.

It all really started with, The Springs, the name we gave to a mid-century inspired lamp from our The Tradition of the New collection. It is also the title of a painting, painted by a friend in 1983 that hangs in our kitchen. The Springs, a quiet little Long Island peninsular hamlet not far from the village of East Hampton, was notable as a location where many New York School painters who came into prominence in the 1950's spent their summers or in some cases lived year round.

More than just a place, it is a source. The Springs represents an attitude, a way of living, a feeling.

Its name derives from a natural spring that fed a small creek draining into the Accabonac Harbor. Accabonac, a name coined by the indigenous Montaukett, roughly translates as "root place" a reference to potatoes - ironically a mainstay cash crop for many years in the area.

The hamlet was once largely populated by working class families of farmers, clammers and fishermen who were named for the harbor where they made their living. 'Bonackers' were descended from families that came from England and settled the area in the 17th and 18th centuries.

The Springs was an authentic, unspoiled and under-discovered place when the artists began to arrive. A nature filled area comprised of hard working families and inexpensive properties - making it all very attractive to a struggling New York bohemian population anxious for relief from the city. We had similar romantic notions and pocketbook to match in 2001, when we made our move to far-flung coastal Maine.

The art critic, Harold Rosenberg and his wife, the writer, May Natalie Tabak, were the first from the New York scene to buy a house on Neck Path in 1944.

Though we never met him, Harold was the friend of a friend. His writings about Post War American art have become an indispensible part of our inspiration. One of the prized books in our library is a presentation copy of his 1959 tome, The Tradition of the New (the namesake of our collection). I purchased it as a gift some years ago from a local East Hampton art book dealer - it was from, Rosenberg's own private collection. The title page quote by 19th century Scottish writer, Thomas Carlyle, could describe our philosophy and the genesis of our collection. "There is a deep-lying struggle in the whole fabric of society; a boundless grinding collision of the New with the Old."

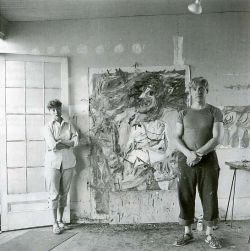

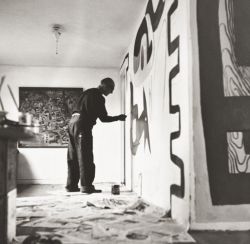

Next to be drawn to the neighborhood were friends of the Rosenbergs, the painters, Lee Krasner and Jackson Pollock, who bought their old farmhouse on the Accabonac Creek in 1945. It was a place to get away from the pressures of the city and just work at the work. Pollock, with his working class aspirations, is famously said to have asked a local, " How do I become a Bonacker? " To which the native replied, "Well first you have to live here about 300 years." This was the start of an art colony that in time included such luminaries as James Brooks, Charlotte Park, Nicholas Carone, Elaine de Kooning, Willem de Kooning, John Ferren, Perle Fine, Franz Kline, Ibram Lassaw, Ruth Nivola, Costantino Nivola, Saul Steinberg, Hedda Sterne and Wilfrid Zogbaum.

Attracted by this long standing art colony, Patrick moved to the East End of Long Island in 1985, settling in Sag Harbor. The Springs would become an often visited spiritual destination. The de Koonings were still there as were Brooks, Fine and the Nivolas. Harold Rosenberg was gone, but May still had the place on Neck Path. Lee Krasner had passed away the year before and the old Pollock home and studio on Springs Fireplace Road sat just as she left them. If one peered into a window one could still catch a dusty glimpse of the domestic life of greatness.

Patrick would become a personal witness to the twilight of a movement. Joining a local art discussion group started by Ruth Nivola, led to a visit to the Nivola's nearly 250 year old Springs farmhouse (with its famous 1950, Le Corbusier mural) that included a chat across the kitchen table, with a compact clear eyed "Tino." His energetic and gregarious personality would provide a sharp contrast to the sweet, quiet and demure, Ruth.

A salient bookstore chat with Elaine, parties at the Richenburgs, openings at Ashawagh Hall, and intimate round table discussions at the newly opened Pollock-Krasner House & Study Center that would attract the likes of Ibram Lassaw, Herman Cherry, John Opper, Mercedes Matter, David Slivka, Paul Brach, David Porter and others; it was this kind of authentic experience that would form the fabric of our feelings about the place.

This summer we spent a month on Long Island to reconnect and recharge. We were feeling nostalgic and wanted to get some relief from the heat - so we took a drive to The Springs. We stopped for an ice cream at the Springs General Store on Old Stone Highway - where a struggling Jackson Pollock once paid his bills with paintings. The antique gas pumps were still there - covered with vines as they hadn't worked in years. Just down the street from the general store we attended an opening at Ashawagh Hall. Perched on a corner of the hamlet's ancient village green, it was a place where many of the early art community once exhibited. Athos Zacharias, de Kooning's first assistant, longtime friend and a maker in his own right, himself made an appearance.

We took a drive past Harold Rosenberg's old property only to find that another precious art shrine had just been demolished to make way for a new home. Further down the road - the Nivola property was undergoing a large barn renovation. The house, done previously, had been moved by the family from its ancient foundation to a drier location, in part to protect its historic mural which had been carefully restored. Sadly, though the table remains in the home, the kitchen, a 1920s addition, has been replaced.

Some say The Springs isn't the same. In an interview in the New York Times in 2001, Clair Nivola, one of the Nivola children, was quoted to say, ''I love the house and the garden but I don't love what's happened to the Hamptons. It's not what it used to be. Something's changed - I weed and repaint, but it doesn't feel like it did before.There's always this slight melancholy feeling.''

Most all of the artists from that golden age are gone. Patrick remembers the last time he spoke to John Opper, not long before he died, when the supremely tired looking artist resting in a lawn chair in his back yard, complained, "I'm just getting too damned old!" Land prices are through the roof, as gentrification and suburbanization are co-opting and supplanting, blue collar and bohemian sensibility.

Though it has now all become art history, the spirit of The Springs remains, in the hearts of those who, even in some small measure, have come to know the place. In every act of quality, the meaning of that name will continue to endure.

(click photo to view larger image)

|

|

|

|

(comments = 1)

I was born and raised on Eastern L. Is.--lived in Water Mill for over forty years before moving to Cobscook Bay area--born to an artist, married to an artist, majored in art; For me "out east" somehow grew into this new geographic area referred to as "The Hamptons" and taken over by all the glitz and status of money and world power. What attracted those artists of the early 20th century to Eastern Long Island can be found here in DownEast Maine--in my humble opinion. 1804

leave a comment

fineartistmade blog

A journal about home design, gardening, art & all things Maine. Read more...

- June 2025

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- November 2021

- May 2020

- October 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- September 2018

- April 2018

- December 2017

- August 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- December 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- April 2016

- November 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- March 2015

- October 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- July 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- August 2012

- June 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- October 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- My Scandinavian Home

- Daytonian in Manhattan

- {frolic!}

- I Married An Irish Farmer

- Smitten Kitchen

- The Curated House

- even*cleveland

- Mary Swenson | a scrapbook

- Ill Seen, Ill Said

- Gross & Daley Photography

- Remodelista

- Abby Goes Design Scouting

- Mint

- the marion house book

- 3191 Miles Apart

- Svatava

- Katy Elliott

- Poppytalk

- Kiosk

- decor8

- KBCULTURE

- Lari Washburn